Pappou’s pites: How my grandfather is making hortopita and kreatopita at 93

A story and a couple honest recipes.

Pappou’s hortopita/spanakotyropita.

Let’s start with a quick disclaimer. This is a piece about my grandad and how he makes pites (pies). Although this is a great glimpse of the traditions and methods he has carried forward from his life in a typical Greek village, Carolina Doriti once said she had recorded at least 370 different traditional Greek pites. Of those, each family, village, and region will have their own idiosyncrasies, tricks and way of making many of them. As will each individual. This isn’t necessarily a recipe for a ‘village pita’ or an ultimate guide to making a Greek pita (if such a thing exists). Nor is it a perfect recipe with a perfect outcome. Some people will do things differently, myself included, and I have left some notes in the recipes to show where and how they might do so.

Very simply, this is a story about Pappou, the fact that he still manages to make pites at 93, and a couple of his recipes.

Here are a few words about him first.

From Aitoloakarnania to London

Although Yiayia (from Limassol, Cyprus) is the culinary matriarch of the household and family, Pappou loves to cook. He is from a village in Aitoloakarnania in Greece, somewhere near Nafpaktos and Messolonghi. To cut a (very) long story short, he moved to London over half a century ago. He still lives in London but, if you were to ever meet him, you wouldn’t be able to tell that he has now lived most of his life outside of his beloved patrida.

As our family has expanded and diversified, with younger London-born, native English-speaking generations plus friends and family members of different ethnic backgrounds, Pappou remains steadfastly, stubbornly, unapologetically Greek. It doesn’t matter the colour of your skin or your age, if you have the pleasure of sitting in his firing line, he will speak to you in untranscribable Greek. About anything, but usually football. If you try to tell him that you don’t speak Greek, he will respond by speaking to you in Greek. Even if you speak fluent Greek, he speaks undecipherable village Greek. There are times when our cousins who have grown up and live in Greece don’t understand him. There are times when I wonder how we do.

Despite having survived a stroke over 20 years ago, you will see him catching the bus in Palmers Green with his walking stick and flat cap. Come rain or shine, he insists on going to Aroma Patisserie, ‘the kafeneio’, or the Greek Cypriot community centre in North London. He sits at the front of the church and makes his presence known when he arrives, often leaving in a similar fashion. At least, all of this was until very recently – he can’t walk far anymore. When he’s home, he calls as many family members as he can, at regular intervals, while watching television on full volume (he presses the ‘volume up’ button on the remote control so much that it once got jammed inside the remote).

Once in a blue moon, he will still cook what he can (with Yiayia’s help). When I began asking him about his recipes, I saw a glint in his eye. He ended up insisting that we make his kreatopita (meat pie) together. I think it reignited something in him, and he has since been cooking again, even now that he finds it harder to stand.

He loves and adores Greece. It’s painful to see him reach an age where he is unable to return every year like he always would. Actually, it bothers me that he’s no longer able to live the rest of his life in the country he loves. As the things we chase eventually fade away, it’s the things we neglected in the process that end up meaning the most. The things we all took for granted as kids – our grandparents’ healthy, hearty, home cooking, the organic produce from their gardens, the gemistá and the fakés we learned to love when it was (almost) too late – are the things we’ll miss the most when the trends and innovation we chase after fade or go out of fashion. It’s no coincidence that Pappou is still going strong, and still cooking, at 93.

So, in the interest of not letting those good things fade or fall behind, of not letting that healthier, tastier (less commercialisable) way of living go out of fashion, here’s a small contribution to the extensive body of work documenting and preserving the foundations we wouldn’t be standing without, in the hope that it continues growing. While it might not be cool to record your grandparents and put them on social media for likes because it looks wholesome, I believe that learning and sharing their strength, their wisdom and listening to their life lessons is of virtue. A big part of that is understanding how they cook and eat – or their determination to carry on cooking well into their 90s. They set us a great example, and we owe much of what we know to them.

Operation Kreatopita

When Pappou and I arranged to make the kreatopita together (plus a hortopita – horta meaning greens), he was looking forward to it so much that he’d mention it multiple times every week, to everyone, until we managed it. With his shopping list, I passed by the butcher’s and greengrocer’s and headed to his house with my cousin to see how it’s done.

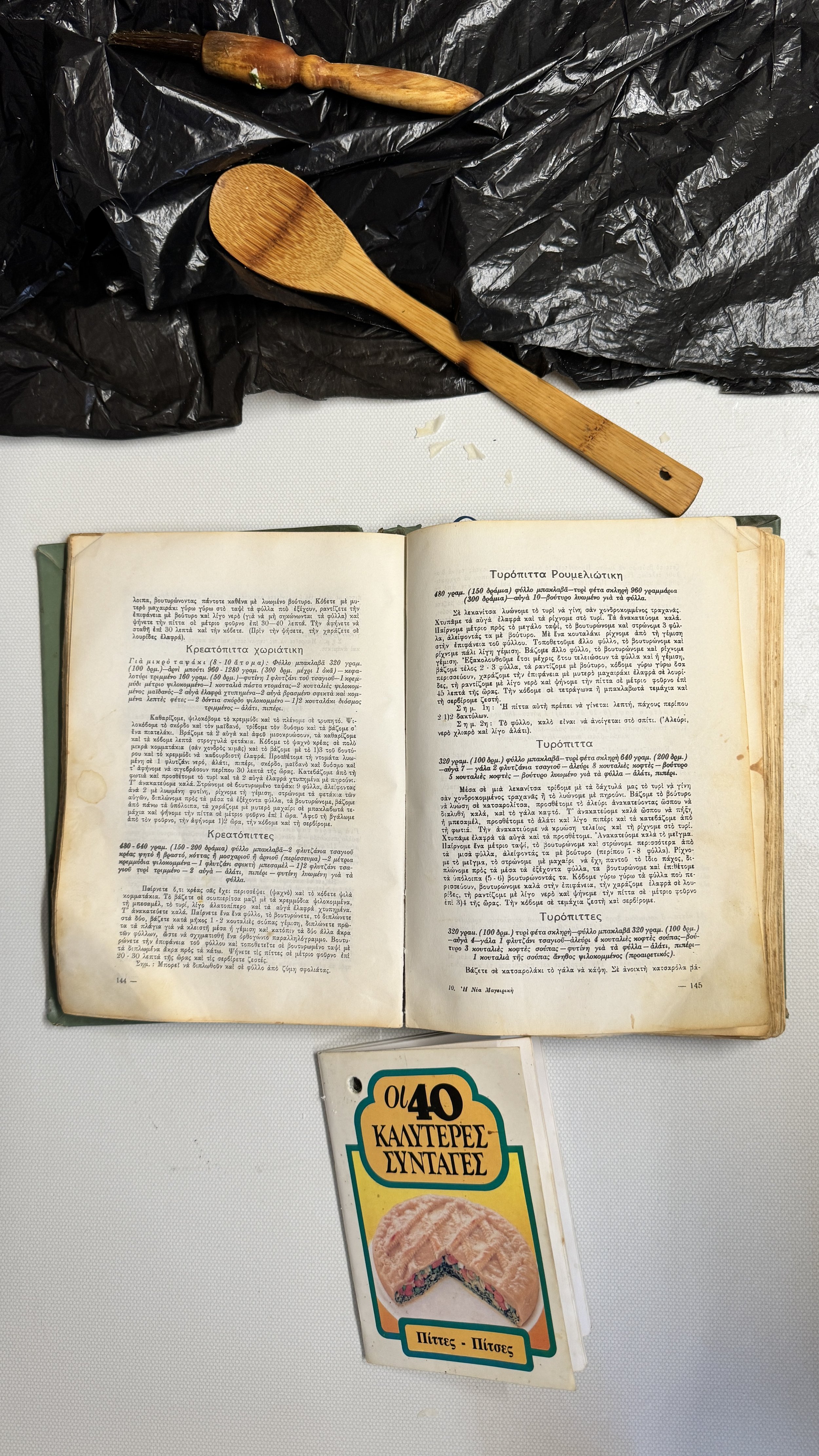

I’ve written a couple of recipes to reflect exactly how he made the pites, without alterations, and have added a couple of notes for context. For example, traditionally, there was no ready-made fyllo pastry in the village, but it’s a bit difficult for Pappou to open the fyllo himself now, as you can see in the Instagram video. Although he uses ready-made fyllo, like many of us will, the traditional ‘village pita’ will involve making the dough and ‘opening’ the fyllo from scratch using a long, thin rolling pin.

Like most Greek food, it’s surprisingly simple, but surprisingly difficult to replicate in terms of flavour. However, I think I’ve figured out Pappou’s secret: he adds loads of salt and doesn’t rush things. And – most importantly – he doesn’t take advice from anyone.

Yiayia allowed Pappou to run the kitchen for a day but was there to hold it all together at every step.

Pappou’s Kreatopita Recipe

Any complaints, speak to Pappou. And good luck.

Ingredients

1-2 pack of filo pastry

1.5kg of thinly diced pork

5 white onions

Greek trahanas (not to be confused with the Cypriot kind more popular in London, nor Cretan ksinohontro, which come in larger pieces rather than grains)

Method

Begin by dicing the pork into 1cm cubes and cutting the onions into eighths. Place the pork in a pot and cover with water. Bring the boil, add the onions and a lug of oil ‘to stop it sticking at the bottom’, as Pappou said. Cover with the lid and simmer until the onions soften.

Season, remove the lid and leave to simmer until the water evaporates and the onions are soft and mushy. The meat and onion filling should be smooth and rich but not dry nor watery. Pappou insisted on not rushing this step but went to sit down and almost burnt it. Transfer to a bowl and set aside, allowing it to cool for a bit. Don’t discard the pot, you will use the remainder to make a jus. Cover the residue with water, give it a stir, bring to the boil and simmer, occasionally stirring and gently scraping any bits stuck to the bottom. You will use this later.

Once the mixture has cooled, pre-heat your oven to 170 degrees celsius. Start lining the fyllo in a large, deep baking tray. Depending how much filo you want to use and how many sheets are in the pack you have bought, think about how you are going to distribute the sheets of filo so there are an equal number on the base and at the top, plus 1-2 between the filling. Begin by brushing oil onto the tin and layering the sheets of filo so they are hanging over the edge of the tray.

Once you have layered the base, evenly distribute the filling on top of the base, leaving some distance between the meat, and sprinkle some of the trahana on top. Pappou used his hands for all of this. Place a sheet of filo on top and repeat until you have used all of the mixture. Fold over the hanging sheets into the centre and finish with the remaining filo sheets, tucking in the edges. Brush with oil and place in the pre-heated oven for 30 minutes, until it starts to crisp and turn golden.

Now, take the pot with the jus from the mixture off the heat and stir. Remove the pita from the oven, and gently pour over the jus, making sure not to submerge the pita if there is a lot of liquid. Don’t worry, the trahana will help to drink it all up. Turn up the oven to 200-220 degrees celsius and return to the oven until the pita has absorbed all of the jus and crisped up. This will be another 40 minutes or so.

Remove the pita from the oven, allow to cool for a little while and fully absorb the liquid. Tuck in.

Pappou stockpiles shipments of trahana from Greece. In London it’s not as easy to find as the Cypriot trahana.

A Hortopita recipe, the way Pappou and Yiayia made it

Ingredients

1 pack of filo pastry

1 large bunch of spinach

1 bunch of dill

1 leek

3 spring onions

About 400g PDO feta

2 eggs

Method

Pre-heat your oven to 170 degrees celsius. Wash and thinly chop the greens that you’re using. Yiayia took charge of this department. Some people cook the greens, many strain the moisture out of them, but Yiayia just shreds them.

Mix all of the greens together in a bowl and crumble in the feta. Mix in the eggs, season and combine well. Pappou used a wooden spoon and his hands.

Start lining the fyllo in a large, deep baking tray. Begin by brushing oil onto the tin and layering the sheets of filo on top of each other so they are hanging over the edge of the tray. Depending how much filo you want to use and how many sheets are in the pack you have bought, think about how you are going to distribute the sheets of filo so there are an equal number on the base and at the top, plus 1-2 between the filling.

Once you have layered the base, add half of the filling, place a sheet of filo on top and repeat with the remaining half of the mixture. Fold over the hanging sheets into the centre and top with the remaining filo sheets, tucking in the edges. (Many will cut the pita at this point, before it goes in the oven, so it can release its steam, crisp up quicker and cut easier once it's ready.)

Brush with oil and place in the pre-heated oven for about an hour, until golden and crisp. Remove the pita from the oven, allow to cool for a little while and tuck in.

Other recipes…